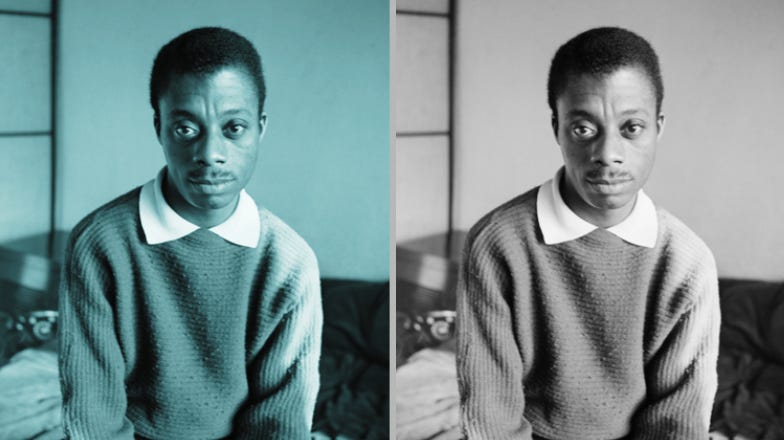

This is the first installment in a series of essays on human beings and the meaning of our suffering, and deals with sensitive issues around self-harm and disability.

“Once upon a time there was someone who somehow did or did not achieve that favorable, no matter how delicate, balance between essential human values on the one hand and cosmic absurdity on the other.”

Albert Murray, The Hero and the Blues

A few years ago, I had the strange little thought that I could somehow become more human. I was slicing up some onions into lean cylinders to simmer into a garlicky mound of oil and balsamic drenched vegetables, each cut feeling smoother and more precise under my hand than the last, when it seemed out of nowhere that the more sensitive and conscious I was of my own experience, with every swift movement of the blade, every slice of the onion, every breath and sensation and change — holding my attention through each little maneuver as one unbroken stream — the more human I was being. Like a high level Jiu-Jitsu practitioner who is at once in the moment while always anticipating the next move, it struck me that there was a right way of doing things that was especially human — at once spontaneous and intentional, natural and planned. An image arose to accompany the thought, too, of the Good Human, someone who is totally present in everything they do. Maybe, I thought, I could become a good human, a real and realized person, awake and alert and alive to everything I am and everything that happens in each new moment, leaving nothing unseen or unfelt.

It was really more of an intuition than a rational thought. How could anyone be more or less human, when we are all already human? How could any of us become more of what we already, in fact, are? I finished up my tasty little batch of glazed veggies, one flavor smelting seamlessly into the next to transform into something altogether new and delicious, but the thought never left me. Certain moments stand out to us, I think, because they come to take a deeper meaning in the narrative arc of our lives, and meaning is revealed only in time.

Strangest of all was the timing of the thought. I was about half a decade into a complex and disabling chronic illness known as ME/CFS (Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome), a post-infection neuro-immune disease that, as far as I could see, had burned my entire life to the ground and left nothing but a little trail of ashes and rubble of a life once lived in its wake. To say the least, I wasn’t feeling like much of a human being at the time. What began as a routine bout with a virus as a teenager has since cascaded into a living nightmare of the human body. The disease drains your essential physical and cognitive energies and breaks down the immune and nervous and endocrine systems at a level that medicine thus far cannot reach to create a situation of permanent disability, pain and malaise that, in my case, seems to only ever and always get worse. My body no longer makes any sense and has devolved into a series of contradictions — exhausted yet sleepless, overheating in one moment and freezing cold in the next, needing of nutrients and yet unable to digest solid food. It is in the nature of this disease for almost any amount of exertion to make the condition worse, what those in the know refer to as PEM (post-exertional malaise), reversing the natural course of human development. This is an anti-human force that eats life.

To put the icing on the cake, ME/CFS just happens to be among the most controversial illnesses in the world, described in a piece last year for The Atlantic as medicine’s most neglected disease. Human beings do not respond well to that which they do not understand, and this disease is little understood as of yet. For reasons having to do with the complexity of the illness and certain blindspots in modern medicine, there is almost no institutional support for sufferers of ME/CFS and we are left to navigate the cold bureaucratic indifference of the American healthcare and welfare systems on our own. Skepticism, disbelief, judgment, even outright venom accumulate between you and the world in the absence of a clear diagnosis or a visible disability. I was shocked and horrified to discover, after first getting sick, that not only did nobody in my life seem to understand what I was going through – or that I was going through anything at all – but the very people who were supposed to help me the most, healthcare providers, were often the hardest to deal with and would form some of my worst and most isolating experiences. When a medical professional tells you that you are perfectly fine when you are most certainly not, it doesn’t feel like the good news they seem to think it is. No one in the world, seemingly, can tell me what’s going on in my body from one moment to the next, and that not knowing kills me.

The whole experience has been absorbed as a kind of loss, of energy, of self, of freedom, of relationships, of meaning, of innocence, of faith, of visibility, of a past, of a future, of a life. The feeling that emerges is one of sheer alienation, from other people, from oneself, and from life itself.

It is in the nature of a virus to replicate and overtake its host. The late Christopher Hitchens, in his final book Mortality (2012) which he wrote while he lay dying of Esophageal cancer, likened his illness to a kind of alien occupation of his body, a little bug or germ. With conditions like mine, it is less of an occupation of an otherwise healthy body than the entire body becoming an alien force against itself. To be sick like this is to feel at once trapped in the body and yet completely dissociated from it – desensitized to positive experiences and hyper-sensitive to the negative. The disease animalizes the person, tethers them to the lowly and base aspects of the human condition and forces them to bear the brunt. As the psychological reactions compound the physical symptoms, what began as a virus of the body soon becomes a virus of the mind and spirit. A little alien emerges from within to sabotage our best efforts, a dark “anti-self” composed of our worst parts that calls itself “you.” The virus replicates and overtakes its host.

By a certain point, everything I came to experience, everything I saw and did and thought and felt, seemed only to remind me that I was alien and inferior, that I was different from and less than other people in some essential way, setting off a vicious cycle of dark and weighty emotions — guilt and shame, fear and rage, and horrible, murderous bitterness — each curdling into the other and coming back to a basic feeling of alienation: of no longer feeling at home in the world or in my body or in this life. To live this way is to be effectively dehumanized, castrated, depersonalized and infantilized, to have one’s fundamental sense of identity and dignity and spirit crushed to a fine powder.

So I was staring down the barrel of a lifetime of disability and suffering and loneliness and shame without reprieve, knowing full well that I would never meet my human potential as a consequence, that not only would everything be taken away but I would be forced to live on and watch. And there were so many things I still wanted in this life. Dying young of my own choosing, to paraphrase James Baldwin, came to feel not like one possibility among many but like the possibility, like gravity itself was pulling me that way. I had become convinced, without hardly a shred of doubt, that if I wasn’t able to recover by my 30th birthday, I would not be alive to see it. I’m 29 as I write this.

Yet there was still my little thought, gleaming and pristine, that I could somehow become more human despite or even because of my situation.

The Human Paradox.

Human. I find the word itself a bit terrifying. Growing up, I never thought much about what it meant to be a person. Like so many of us, I think, I just went with the flow of those around me, staving off any thought that might remind me of how absolutely bizarre everything is. I was afraid, though I never would have put it this way at the time, that if I discovered my connection to other people I would somehow lose my specialness, that by becoming more of a human being I would in turn become less myself. I think we put up walls of differentness, ultimately, to conceal our vulnerabilities and protect us from the forces of other people that most threaten us in ourselves. Dictionary definitions of the word “human” are somewhat vague and circular, referencing amorphous qualities without going into what those qualities are. I wonder if we are so intent on discovering who we are that we often ignore the more vital and disturbing question of what we are.

But the moment we ask that question, we find ourselves staring into a strange abyss, a vortex going all the way down, down, deep into the deep black sea. Like the quivering experience some of us have as children when we catch a glimpse of ourselves in a mirror and are faced for the first time with the sheer absurdity of being anything at all, we are thrown face-first into chaos. What we are looking at in that mirror seems alien and strange to us, like our bodies are not quite our own. What we discover in such moments is the uncanny valley between the images we have formed about ourselves — the familiar name and face and history and all the associations and affiliations of the self — and the living reality of our being. This feeling of cosmic isolation is something close, I think, to what existentialists mean by The Absurd, the feeling that we are somehow separate from life. And even stranger, this feeling of alienation would seem to be especially human.

It seems to me that human life is a kind of paradox that spirals out into other paradoxes and bleeds into everything we see and do. Much is captured in the term “the human animal,” which implies both a fracture from and meeting ground between our visceral bodily instincts and our higher humanly hopes and aspirations. At once spiritual and carnate, we know we are alive, which means we know we are going to die; we are moral animals that can differentiate between right and wrong, which also makes us capable of evil; we can anticipate the future and reflect on the past without ever leaving the present; conjure and intuit larger spiritual meanings without departing from the physical realm. The human paradox is that we are at once a part of life and apart from life, and it is our uncanny ability to step outside of reality and see things from an alien perspective, to imagine things otherwise, that both makes us human and also makes everything feel so strange and un-homelike. The very quality that makes us human is also what makes us suffer.

The Anti-Human.

“Life eats life to live,” went the Serbian poet Dejan Stojanovic, and there are so many aspects of life and the human being which seem to take away from feeling alive and human. In another paradox, there are anti-life and anti-human forces at work in human life — suffering, illness, tragedy, evil, fear, guilt, insanity, death, all of which spell chaos — that are enemy to the human spirit and which make life so strange, humiliating, difficult and terrifying for us. And yet the anti-human forces, too, are human, and the things which seem to eat life are in another sense a part of it.

Reality, according to the Daoists, is an interwoven and balanced system of antagonistic forces — life and death, light and dark, joy and suffering, meaning and chaos, tragedy and comedy, masculine and feminine, universal and particular, self and other, individual and the world, alien and human — that exist only in cooperative tension with each other. In the same way we only recognize light in its contrast against darkness, the self-described “entertainer-philosopher” Alan Watts has observed, we quite literally would have no way of imagining or recognizing anything at all without its opposite. And in the same way we can only hear music through oscillation of sound and silence, it is from the interplay of something and nothing, form and void, the positive and negative principles, that everything in the universe springs into being. Duality is the idea that what seems to be in conflict from our perspective may be health and harmony on a deeper or higher level, and those things which seem on the surface to be the most different actually share an underlying and essential similarity.

This idea is famously captured in the Chinese symbol of Yin and Yang, in which a white swoosh with a black dot is counterposed with a black swoosh with a white dot to indicate the interconnectedness of opposing principles, with the dots in each swoosh conveying that light can turn to dark and dark can turn to light and there is a bit of light in every darkness and a bit of darkness in every light. There is a point at which the opposites of life come together on the razor’s edge of reality, the border between Yin and Yang, where dark congeals with light and light with dark and where meaning and chaos swirl, and it is at this neutral point at the center of everything where reality is ever unfolding and where it can be accessed. And while we naturally reach for the light against the darkness, prefer joy to suffering, life to death, meaning to chaos, this, too, is human. Even more human, I think, is the act of bringing darkness to light and drawing light from darkness.

It is a truism of psychology that the darkness we fail to appreciate in ourselves gets unconsciously projected onto the world and inflicted on other people. For instance, it is often those who are most convinced of their innocence that are the most dangerous in actuality, while those who tend to feel more guilt in general are often less harmful. An excess of innocence is dangerous, in other words, and I think evil always disguises itself as The Good and arises from the least explored parts of ourselves. The more we deny and repress our own darkness and pain, I think, the more pain and darkness we bring into this world. The idea of balance implies more than just a happy medium between opposites, but something closer to the psychological concept of individuation, absorbing and integrating the darkness into light by shedding light on the darkest parts of ourselves. What we discover, ultimately, is there’s nothing to really be afraid of.

Applying this principle, the great American novelist Ralph Ellison (Invisible Man) and his good friend and fellow literary man Albert Murray (The Omni-Americans) had this wonderful idea of “antagonistic cooperation,” possibly lifted from Joseph Campbell, which goes that we need antagonizing forces in life with which to confront and do battle and this battle becomes, in another paradox, a form of cooperation with the antagonist: Using the fact of suffering to savor moments of joy, the fact of death to live more fully and the fact of fear to act more courageously. We need suffering and conflict and danger and darkness and death and tragedy and horror in order to face these things and squeeze from them the kind of heroic and transcendent heroism that is the essence of great art and story. There is quite literally no meaning without chaos from which to extract it, no joy without suffering with which to compare it, and no morality without a sense of evil to contrast against it, and it is often the very things we find most frightening and painful and strange and embarrassing about ourselves and about life that, by looking at them, make us feel a bit more human.

Acceptance and Change.

Life is suffering, and even the best of lives are touched in some way by the human tragedy. No one is truly safe from anything in this life. We lose someone. We get sick or injured. Disaster strikes. There’s a crisis. Someone wrongs us, hurts us, disappoints us, destroys us, and it can be extremely difficult to accept these things and come back from them to feel human again. Suffering doesn’t usually make us wiser or deeper or stronger or better people but very often makes us worse and weaker and harder to deal with. The reservoir of human suffering is bottomless, and some people never get back up from the things that happen to them. It can be horrible to realize just how vulnerable we are to absolutely everything.

Something strange and unexpected happens, however, when we come to accept the worst possible outcomes in our lives: We change. There is a great deal more power and possibility in the act of surrender than we typically assume. In the same way we can’t solve a problem until it is named, I don’t believe we can change anything about our lives until we have accepted our lives as they are, and cannot change anything about ourselves until we accept ourselves as we are. Accepting a painful reality that we have long been repressing releases the energy to see it more clearly and possibly change it that was otherwise wasted in denial and escapism. “Not everything that is faced can be changed,” wrote James Baldwin, “but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

But how do we do acceptance and change? How do I accept having a potentially life-long illness and disability that is almost completely invisible to others, routinely denied, often misunderstood and by its very nature alienating and inferiorizing, all the while dealing with all the complications and pressures of a life? I don’t know how to accept any of this. I think I’d rather die than accept it.

Yet people do accept these sorts of things, and are in turn changed by them. “The acceptance of the unacceptable,” wrote the Sufi poet Rumi, “is the greatest source of grace in this world.” It is by no means unheard of for people who have endured the worst possible situations to develop from them the best possible attitudes toward life, completely reversing how so many of us view the relationship between happiness and adversity. It is often those souls who have gone through the unthinkable, a debilitating injury, false imprisonment, a terminal or chronic illness, some sort of heavy loss or cosmic injustice, those things in life we can never quite prepare for, who come back from it with a renewed sense of life’s meaning and what can only be described as a more spiritual attitude.

“Suffering is the sole origin of consciousness,” wrote Dostoevsky. It was in the dark smog of the concentration camps that the young Austrian psychologist Viktor Emil Frankl discovered the innate human capacity to surrender to and ultimately transcend the tragic circumstances of our lives, drawing possibility from limitation to bring about a new sense of spiritual freedom and responsibility. “When we are no longer able to change a situation,” Frankl wrote in his classic Man’s Search For Meaning, “we are challenged to change ourselves.” This is not too far from the overriding message of many of our great spiritual teachings — God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change… “Has all this suffering, this dying around us, a meaning?” Frankl asked himself in the concentration camps. “For, if not, then ultimately there is no meaning to survival… If there is a meaning in life at all, then there must be a meaning in suffering.”

There are countless examples of light emerging from the darkest of places, like a candle in an unlit room. Consider what often occurs after the most recent public tragedy or act of violence, and the outpouring of humanity that very often emerges in its wake. There is something almost natural and autonomic about that kind of humane reaction to so much darkness, as though the only sane response to inhumanity is more humanity. Or think about survivors of self-annihilation attempts who speak of the overwhelming regret they felt in those moments they thought were their last and the rejuvenated will to live that emerged in its wake, so powerful that most of them never again make another attempt on their lives. Or the moment the Christians describe of being saved after having a dark night of the soul. Or consider the art form of the blues and jazz that emerged from the thresher of black American history and culture, the essence of which is to overcome suffering by seeing and stating it clearly to squeeze some comedy out of tragedy and make meaning of the absurd. It seems the act of drawing light from darkness, far from the exception, is something close to a natural law. But first we must surrender to whatever circumstance we are up against, which is to say, accept reality, before we can change it.

In the spirit of surrender, I haven’t felt like a human being in a long time. The alien force of this disease, the little germ, has overtaken me, has become me, and the poison has spread throughout my life and infected everything. There has been a darkening, a shutting down and cutting off from life’s natural rhythms. I’m all fucked up and broken inside. Something in the human soul revolts from always wishing and hoping for things to get better and watching them only ever and always get worse. Severe and abiding suffering, without relief or meaning, can easily curdle over time into darkness, and if I’m being honest, I’ve become a bit evil in some ways. I don’t always wish the best for people, especially those who have hurt me in some way, and sometimes I even feel the urge to take revenge on one or two of them. But typically, that darkness is inverted inwardly on myself. The will to self-annihilation has been so intense at times that it has felt as visceral as thirst.

This is what alienation does to a person: It makes you literally crave non-existence. And it really does behave like a virus. Once a person becomes dehumanized, it is easy to dehumanize ourselves and other people in how we see things. Feelings of alienation and smallness crystallize into an identity, something we feel some sense of attachment to and ownership over and are even willing to defend. And this is a very dangerous moment, because that pain, that little alien, has a life of its own that is very much against ours. It calls itself “you,” but it isn’t the whole of us. The virus replicates and overtakes its host. Alienation is not simply the state of being cut off from the world or from other people but from the human experience itself, to lose not only our sense of who we are but more deeply our sense of what we are.

There was a time when I still held out hope for recovery, when I still vaguely felt a part of this world and this life. The intervening years have seen a slow falling descent into worse states of bodily and mental health with brief periods of stability before things just get worse again and throw me back into chaos and despair. This year was much worse than the last, last year was much worse than the year before and so on, for about a decade. The last few years have seen the worst of it, the past few months in particular, and I’m arriving at a point where I cannot literally imagine living on like this. This past winter was for me symbolic of what James Baldwin once called the long hard winter of life, the breaking point of no return. A human being can only take so much before something in them shatters and they react in some horrible way, just to feel some sense of power over our lives and our bodies. I’m always kind of girding myself for something terrible to happen.

Perhaps it’s already happened. As hard as it can be to change, it’s sometimes even harder to realize how things have already changed, how we have already changed and have just been slow to realize it. I’m beginning to remember things outside of this illness. I’m beginning to remember what it felt like to be human. As strange and surreal as it may seem from the vantage of my mind, everything that has happened over the past decade with my condition has really happened, has all been real, and with that comes a sense of urgency. The closer I’ve come to dying, in a way, the closer I’ve come to living, and we are always, in a sense, living and dying to who we once were and being reborn anew. And I wonder if life really is just this constant living and dying, this endless forgetting and remembering of who and what we are, coming untethered from life only to feel a part of it all once again. As for now, I’m living for the possibility of feeling like a human being again.

Alienation and Humanism.

Alienation is not just my problem. It is a human problem. And the antagonistic counterpart to alienation, I think, is humanism. Humanism can mean different things to different people but my meaning is quite simple: The human being is the seat of everything of meaning and value in this world and there is nothing more precious and important in the universe from our perspective than each other. This, of course, does not exclude a love of nature or animals or a fascination with what else is out there, but these inclinations, too, are human, and if human beings are the major source of light in this world, we are also the source of much darkness.

Human beings are complicated and difficult and weird and dark and beautiful and interesting and highly sensitive and impressionable and we have sharp edges and complex aims and are absolutely brimming with paradox and contradiction. There are anti-human forces at work within the human being itself, most of which come down to various forms of black-and-white thinking, the denial and avoidance of reality. We like power and control, which often means denying our vulnerabilities. We tend to essentialize individual behavior and put people in categories of good and bad, superior and inferior, which means denying our underlying sameness. We thirst for innocence and certainty, denying our inherent guilt and ambivalence. We mistake paradox and differentness for an essential and irreconcilable conflict, denying the connection between people and things.

Ultimately, I think humanism is about facing the things in ourselves and the world that we would prefer not to look at and which prefer not to be looked at — taking account of our flaws and blindspots and evils to ultimately harness and cultivate the strength and courage and wisdom and beauty and goodness of human beings. In a phrase, because of how fallen we are in so many ways, the harder thing to do is often the right thing to do, while the morally easy and convenient thing to do is usually evil and anti-human, which are more or less the same thing. Any time we care about something more than actual human beings, the outcome is darkness.

What is required to counteract the dehumanizing forces of life and our lives is a commitment and devotion to the inherent value and dignity of the human being, our depth and complexity, our sacredness and beauty, our freedom and fulfillment — “freedom which cannot be legislated,” James Baldwin once wrote, “fulfillment that cannot be charted.” Humanizing something, crucially, doesn’t mean tolerating it, just understanding it on a human level. It is quite human to be appalled by evil. But if the evil within is left unseen and unchecked, what seems like a righteous crusade can swiftly turn into an atrocity.

The best declaration of humanism I have ever heard came once again, unsurprisingly, from Baldwin, who said in a 1963 interview, “I suspect every novelist has just one message. And that would be the very dangerous effort one has got to make, according to me, to deal with other people as though they were simply human beings. To remember that no matter what the details of their lives may be like or how different they seem to you superficially, or what the social pressures are outside or what the psychological pressures are within. To deal with this other human being precisely as though, as it is true in fact, he or she was here for the first time, and the only time. To deal with them in some way how you want them to deal with you. And no matter what price.” The Golden Rule.

“From my point of view,” Baldwin went on, “no label and no slogan and no party and no skin color and indeed no religion is more important than the human being. [To search out] the human core in everybody. It liberates you, if one can do it, and it liberates me. Because when the chips are down, this is all there is. There isn’t anything else.”

Among the dark and dangerous tendencies of human beings is that of elevating ideological abstractions above the living reality of other people, with typically horrifying consequences. To escape our own pain and vulnerability and darkness and limitation, we project an idealized image of ourselves that is more than human while grafting a mask of inhumanity over the faces of those we deem less than human. For one individual or group to become more than human, which is to say, perfect, another must be seen as less than human, and in many cases this is enforced from above to make the metaphor literal.

The classic example in the U.S. is the case of American slavery and Jim Crow segregation, in which black Americans were seen in the collective imagination as subhuman animals to justify their treatment and place in the social and economic order. This is what we do: We cannot justify destroying another person unless we first believe they are unlike us in some essential way, and from here comes all of the historical justifications of oppression. As Baldwin has elsewhere observed, it is psychologically and morally impossible to debase and degrade another human being without effectively destroying our own humanity. Baldwin would often observe how, in many ways, the perpetrators of racism were worse off in spiritual and moral terms than its victims.

The second portion of Baldwin’s quote is just as powerful. “It seems to me that the whole effort is not to avoid suffering, or the inevitable deformations which one encounters in a life, but to use them. To use one’s suffering to understand the suffering of other people. And to understand that though you have lost some things because you were born where you were born or because of who you became, you have gained some other things. I think it is adolescent to look back and wish things could’ve been different. You have to make the most, precisely, of what it is.”

Humanism, in practice, is about using our own experiences and our own suffering to come closer to the experiences and suffering of other people and perhaps to the human experience itself. Our suffering is not just ours but belongs to the world. “The world is you, and you are the world,” went the Eastern philosopher Jiddu Krishnanamurti. “Realizing that fundamentally, deeply, not romantically, not intellectually but actually, then we see that our problem is a global problem. It is not my problem or your particular problem, it is a human problem.” This comes with a sense of responsibility that will mean something different for each of us.

Before I can change anything about my life, I have to accept reality and everything that’s happened to me over the last decade with my illness, to accept myself as I am and my life as it is, to accept that I am going to be misunderstood and misjudged by the world, to accept all the pain that has accumulated over the years and that I’m still alive and human despite it all. The effort is to find what is human and humanizing about this alien and alienating situation. If all this suffering, this alienation, has no meaning, then life has no meaning, and I’m not willing to accept that just yet.

For years I’ve been running from the true meaning of this experience, but I can no longer afford to stave it off. Certain anti-human tendencies have taken hold of me that, while no doubt initiated and inflamed by my illness, have come to take on a life of their own that now pose a genuine threat to my life. It is not easy to admit that I might have problems outside my disease when it has taken so much from me and when seemingly the entire medical apparatus of my country is intent on denying the biomedical reality of my experience — without which it is impossible to understand me as a person and the adaptations I’ve made to survive. And yet how can I ask other people to accept the reality of my condition if I haven’t even fully accepted it? What is being asked of me, I think, is to accept reality without ever giving up, to separate the virus from my deeper sense of life, and ultimately melt the little alien inside with the light of conscience and consciousness.

What stands out whenever I reflect on the past is always where I was at in the course of my illness at a given time, not whatever else was happening in my life. But there were other things happening. There always are. There is a story to my life that goes beyond the timeline of this illness, a human weight beneath the symptoms. Even during this decade spanning bout with disease, I have lived, had relationships, grew, learned things, about life, about myself, about the world. Everything that has happened to me, as strange and difficult and terrifying and painful and outright embarrassing as it’s been, has been human, and nothing human, went an ancient playwright, is alien to me. When we can see and articulate the dehumanizing forces of our lives, they are immediately humanized. The way back into life after falling out of the world is to become more conscious and sensitive to all the things that alienate us from other people and our own inner spirit.

I’m looking for my way back in: Into life, into the world, into my body, into myself, into being human again. I once believed my illness cut me off from the human experience, that the specific conditions with which I was faced somehow disqualified me from being a person. I’m wondering now, just now in fact, if it’s done the opposite, if all of this suffering has been my own initiation into the human experience that I never wanted but always needed. My illness is just an intensified version of the human condition, in all its fragility and resilience, and all of the feelings I’ve described are human feelings. And it may sound strange to say, but I am actually proud of myself for having lived through this and grateful for what it’s taught me. Because, to quote a now controversial artist, “When the shit hits the fan, everything I’m not made me everything I am.”

Going back to my little thought at the beginning, what could it mean to be more human? It certainly doesn’t mean anyone is any more or less human than anyone else. But isn’t that, in itself, a humanizing statement, more or less so than others? Some things are more human than others: We can see and feel and act more humanly. The import of my little thought was simply that it does mean something to be a person and we can get closer to that meaning by bringing attention to our own experience. And even in suffering, there is still meaning to be had. I think every situation has one most human response that stands out as the most personally meaningful. “What is most personal,” went the famous Carl Rogers quote, “is most universal.” And the anti-human forces of life, too, are human.

That’s a paradox, but a paradox is not a contradiction, only a seeming contradiction: something which seems not to make sense but carries deeper meaning. I think being human means being suspended between different and opposing forces, and the most human thing to do is embrace life’s paradoxes and uncover the hidden meanings and connections: Drawing light from darkness, beauty from horror, comedy from tragedy, universals from particulars, power and possibility from vulnerability and limitation, and to take something of essential human meaning and value from the dehumanizing and chaotic forces of our lives. It means using our suffering to change for the better.

Although we can never quite put it to words, I think all we know, on some level, that what we are is deeply special, that this life is deeply special. It is something in the eyes, something in our faces. It’s been said that when you are staring another person in the eyes, it’s like the universe itself is looking right through you. We are these sensitive, vulnerable creatures with fleshy bodies and penetrating spirits that can change our reality simply by looking at it, both shaping life and in turn being shaped by life. At bottom, we are the energy produced by our attention, and when we attend to our own lives, leaving no thought or feeling or experience unseen, we connect with the force of life within us to feel a part of everything else.

Nothing can ever truly separate us from life, for we belong to life and life belongs to us. There may be nothing more human than feeling subhuman, except coming back from those feelings to feel a part of life again. We could all be a bit more human, and while along the path we will stumble and fall, this, too, is human. No matter what becomes of us, we are still human. Nothing could ever change that. Nothing more and nothing less than human. Still and always human.

James Baldwin expressed humanism as well as anyone. Thanks for sharing his lovely statement of the Golden Rule.

Beautiful essay, Samuel. Magnificent. You so eloquently write of concerns and the questions I've been considering. Thank you.

I have had Long Covid for over a year now. It stopped me in my tracks. I feel as though I am frozen in time. I only exist outside of society.

Love and wishes for peace to you, fellow traveler, and some day soon...healing for us all. Solidarity.