I wanted to share my essay on the psychologist, author and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl that was just published for City Journal. For everyone who has subscribed over the past couple weeks, I’m so happy to have you here and it really means the world to me. I generally write about human suffering and meaning through my own situation with illness and disability, and the idea of this Substack is to connect my experience and my suffering to the human experience and the suffering of other people. None have provided more clarity in that effort than the good doctor Viktor Frankl.

Frankl’s take on human suffering and meaning has helped me understand the meaning of my own suffering, and this entire project owes him a great debt. If he could survive four concentration camps, lose his entire family in the Holocaust and come back from it to produce some of the most inspiring nonfiction of all time, effectively using his suffering to help other people find the meaning of their lives, well, I can at least try to face my situation with some of the same courage, wisdom and grace with which Frankl faced his.

Below are a few lightly edited excerpts from the piece, and selfishly I recommend reading it in full if you haven’t. It was a very meaningful one for me to write, as anything I write having to do with Frankl tends to be. The feeling you get reading him is that no matter what life throws at us, we are still and always human — and more, it’s possible to use what life throws to more deeply realize our humanity. Frankl is probably the most inspiring person I’ve ever heard of. I may be at the darkest point of my journey now, but Frankl’s work never fails to remind me that the meaning of reality extends far beyond our limited perception of each moment, beyond time itself. So long as we are still alive, there is hope and possibility yet. If there’s a singular takeaway from his work for me, it’s simply this: It’s not over until it’s over. Don’t ever give up.

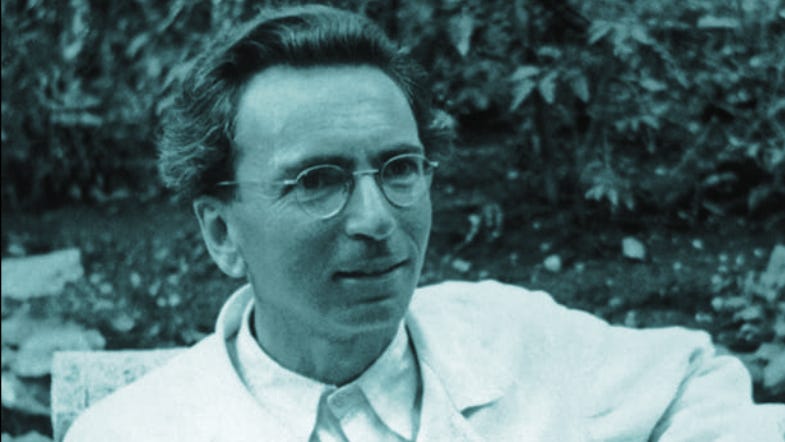

Viktor Emil Frankl was the quintessential humanist. His memoir Man’s Search for Meaning, a psychological portrait of life inside the concentration camps, has become a go-to for seekers of every variety since its original German-language publication in 1946. Listed as “one of the ten most influential books in the U.S.” in 1991, it still appears as one of Amazon’s 100 Books to Read in a Lifetime. This “should be required reading for anyone desiring to live on this planet,” says a YouTube commentator beneath one of Frankl’s interviews.

Frankl was concerned with the meaning of human suffering. Unlike camp inmates Primo Levi and Elie Wiesel, who grew understandably despairing in the years after Auschwitz, Frankl lived and died a happy man. Despite the horrors of what he saw and experienced in four concentration camps over three years, Frankl never lost faith in mankind. While suffering can make us feel less than human, Frankl used his to understand the pain of others and become, in a sense, more of a human being.

While most written accounts of the Holocaust emphasize its obvious racial and political dimensions, Frankl always sought out the uniquely human quality of any situation to draw out a universal message. His vision of a human-centered psychiatry that would counteract the depersonalizing forces of modern life may never have fully taken hold, but its urgency has only grown with time.

On Family

Frankl loved his family ferociously. In his final memoir, Recollections (1995), where he shares more about his private life than elsewhere, Frankl describes his mother as a warmhearted, pious woman and his father, who worked for the state on various relief programs, as the personification of justice. His father once rescued a toddling Viktor from an oncoming train after the child had scurried onto the tracks, a memory burned into Frankl’s consciousness. “With my eyes still closed,” he remembered, “I was flooded by the utterly rapturous sense of being guarded, sheltered. When I opened my eyes, my father was standing there, bending over me and smiling.”

When his father was afflicted with pulmonary edema in the camp, Frankl used a smuggled vial of morphine to ease his pain.

I asked him: “Do you have pain?”

“No.”

“Do you have any wish?”

“No.”

“Do you want to tell me anything?”

“No.”

“I kissed him and left,” Frankl writes. “I knew I would not see him alive again. But I had the most wonderful feeling one can imagine. I had done what I could. . . . I had accompanied my father to the threshold and had spared him the unnecessary agony of death.”

This was Viktor Frankl: a man who could squeeze out a moral victory from the death of his own father in a concentration camp.

On Suicide

Between the wars, Frankl gained valuable experience working at a youth counseling clinic dealing with teen suicide. It’s a testament to Frankl’s humanism that he took an unequivocal stance against suicide in almost every instance. Frankl would even develop a procedure, using amphetamines, to revive people who had attempted suicide. “I take the position that even in the case of an actual suicide attempt,” he argues in Yes to Life: In Spite of Everything (1946), “the doctor not only has the right but also the duty to intervene medically, and that means to save and to help if, and to the extent that, he can.”

The nihilism of the modern age that lacked moral concern for suicide, Frankl later argued, was, at bottom, the same antilife sentiment motivating Hitler’s euthanasia programs.

In Yes to Life, Frankl takes us through the counterarguments to the proposition that life has intrinsic value, going through all the ways that life could be stripped of sense—incurable or terminal illness, mental illness, disability, loss, imprisonment, sterility—to make a case for the inherent sanctity of life. No amount of anguish or adversity can truly take away our humanity, he says. Being human precedes our capacity to be productive, functional, or even mentally sound.

On Meaning

Frankl eventually broke with his two mentors, Adler and Freud, and the schools of psychotherapeutic thought they represented, and would form his own: Logotherapy, which orients patients toward a sense of purpose to be fulfilled in the future to overcome the misery of the present. It’s about getting people to realize that something awaits them, that something is expected of them that they, and only they, can actualize. If traditional therapy is about depth, a peeling back of layers until we get to the truth of who we are, then logotherapy is about height, a reaching upward for our greatest potential.

While Adler saw the will to power as the central motivating force in our nature, and Freud saw pleasure, Frankl argued that we are willing to forgo power and pleasure if it is meaningful to do so. As far as Frankl could see, the excessive pursuit of pleasure and power so common today is mere compensation for a lack of deeper value in our lives. With a good enough story about who we are and wish to be—a story that ties our personal journey to mankind’s larger story—we can get through pretty much anything. As Nietzsche put it, “he who has a why to live for can bear almost any how.”

A key aspect of Frankl’s vision is that meaning does not emerge in a vacuum or within the circular confines of the self. We exist in relation with others; we are not closed loops. While much psychotherapy is a roundabout effort to perfect or modify the self, Frankl recognized that the significance of life is to be found through our relationships with the world and other people. One could even say that the meaning of life is other people. Self-transcendence is the essence of logotherapy.

On Suffering

While previous schools pathologized suffering, Frankl argued that not all forms of suffering are necessarily pathological or neurotic. Indeed, it may well be a sign of an existential problem that helps us understand the purpose of our lives.

In Frankl’s view, mental well-being comes through pursuing worthwhile life goals, rather than pursuing happiness itself. Happiness is not something that we can successfully pursue; it is something that must ensue. He took issue with the strain in psychiatry known as “unmasking,” in which everything a patient says is seen as a mere rationalization of deeper instinctual drives that he is afraid to face.

Frankl understood that finding meaning in life can often create conflict, friction, and even pain. By orienting patients toward a positive future that gives their lives purpose, logotherapy creates a tension between who we are and who we wish to become. For Frankl, mental health was based on a fluid state of constant becoming, rather than a blissful state of selfhood that no one achieves: “Not every conflict is necessarily neurotic; some amount of conflict is normal and healthy. In a similar sense, suffering is not always a pathological phenomenon; rather than being a symptom of neurosis, suffering may well be a human achievement. . . . A man’s concern, even his despair, over the worthwhileness of life is an existential distress but by no means a mental disease.”

The strain in psychotherapy that puts individual suffering under a microscope, absent any larger spiritual or cultural context—as though every problem you might have has nothing to do with anyone or anything else around you—cuts us off from the deepest wellsprings of experience, in which suffering is universal.

On the Meaning of Suffering

To summarize Frankl’s views: it is the search for meaning, he believes, that makes us human. Life carries the potential for meaning under any circumstance. Every individual problem has an individual solution, an answer or action that stands out as the most significant thing that we could do under the circumstances. As Frankl writes in Recollections: “I am convinced that, in the final analysis, there is no situation that does not contain the seed of meaning.” Suffering isn’t necessary to make this discovery, but meaning can be found despite, even through, suffering, depending on our attitude toward it. The solution to the problem of pain is to become more of a human being by seeking out meaning.

In his writings on the camps, Frankl details the psychological breakdown of the average camp inmate—from shock to despair and finally a strained readjustment to a nightmarish new reality. What made Frankl’s account unique was that he was less concerned with the obvious moral message of the camp experience than with the interior processes of the actual people living in the camps. Most of us are aware of the horrifying conditions of the camps. Lesser known is the spiritual war against suicide that took place daily. Death was waiting around every corner, and there was always the potential death within: the psychological death that often results in a suicide.

What Frankl witnessed in the camps confirmed his suspicion that, in the worst situations, those with a sense of intrinsic purpose were less likely to die. “The two basic human capacities,” he outlines in Recollections, “self-transcendence and self-distancing, were verified and validated in the concentration camps. This experiential evidence confirms the survival value of the will to meaning and of self-transcendence—the reaching out beyond ourselves for something other than ourselves. Under the same conditions, those who were oriented toward the future, toward a meaning that waited to be fulfilled—these persons were more likely to survive.”

Frankl’s Impact

Frankl once received a letter from a man named Jerry Long, along with a newspaper clipping from the Texarkana Gazette of April 6, 1980, telling his story. Long became a quadriplegic after a diving accident at 17 and found inspiration in Man’s Search for Meaning. Using a pencil-size rod with his mouth to write with, he went to school to become a psychologist. His motivation? “I like people and want to help them.” When Long finally met Frankl face-to-face, he told the doctor: “The accident broke my back, but it didn’t break me.”

Countless others could give similar testimonies about how Frankl has helped them endure personal trials. In my own case, having lived with a disability for over ten years due to a complicated neuroimmune disease, I can’t begin to explain the impact that Frankl has had on my own life.

Frankl shared story after story of hardship and transcendence on the part of others—but what was the meaning of his own life? A student at Berkeley gave him an answer: “The meaning of your life is to help others find the meaning of theirs.”

Thanks Samuel for this splendid essay about Frankl. I am always inspired by your writing. Pleased to become a new subscriber after reading your essay about Shelby Steele in Quillette.

Thanks Samuel for a great article which I did read in full. I also read "Man's Search for Meaning" some years ago and found it inspiring. Frankl was an amazing person. I hope that you are finding some meaning in your writing, which is I am sure helping others.